From 'The Rumble in the Jungle' to Poland's "Victorious Draw" At Wembley

Remembering the 50th anniversary of 1974: A Tumultuous year in sport.

In June, 1973, the England football side took a rare peek behind the Iron Curtain. On the face of it, their assignment looked straightforward: to play against Poland in a qualifier for the following year’s World Cup.

They boarded a plane, brushing aside the inconvenient fact that Poland had won the gold medal in football at the 1972 Munich Olympics in West Germany, beating East Germany and the Soviet Union on the way to the final. In the final, they beat Hungary to win the gold medal.

After winning the 1966 World Cup, England believed they were blessed with a kind of manifest destiny. They were coached by World Cup-winning coach, Sir Alf Ramsey.

They had one of the world’s most recognisable players in Bobby Moore in their ranks and an up-and-coming (where did you last hear those quaint three words?) young goal-keeper in Peter Shilton, Gordon Banks’ successor. They would prevail despite being deep in the heart of the Communist world. They were England. After all.

England didn’t prevail in Poland. Playing in the unusual colours of yellow shirts and blue shorts, they conceded the opening goal against the home side, wearing white shirts with red shorts.

And it got worse. In the second-half, Moore received a back-pass from England teammate, Roy McFarland. Normally, Moore would have dealt with the pass with his customary aplomb, but upon receiving the ball this time round, Moore experienced an atypical – a very un-Moore-like – moment.

Moore had always commanded a football but now the football seemed to command him. It got stuck between his legs and, for a horrible instant, Moore looked clumsy. He was dispossessed by the Polish striker, Włodzimierz Lubański, who sprinted downfield and scored Poland’s second goal.

There was elation on the stands. England didn’t visit Poland every day and now, here they were, the 1966 World Cup winners, 2-0 down. When the final whistle was blown half an hour later, the score remained 2-0 to the Poles.

For England fans, it beggared belief. It was a “did-this-really-happen-to-us?” moment.

After the trip to Poland Moore only played three more times for England. All of the matches were friendlies, so the game against Poland in the southern Polish town of Chorzow was his last competitive football for his country.

By the time came for Poland to visit England for the return leg, Moore had retired from the international game. Players like Emlyn Hughes, Liverpool’s so-called “Crazy Horse”, and Leeds United’s Norman Hunter, were preferred instead. Lubański, the Polish striker who had dispossessed Moore, didn’t play the return leg either. He, too, was in the twilight of a long an illustrious career.

Let’s have a listen here to the English commentator as he looks down the Polish team list for the return leg at Wembley, balancing the names he’ll have difficulty in pronouncing with those that are slightly easier to wrap his tongue around.

Despite the 2-0 away defeat, it was widely assumed that the wrongs of Poland would become the rights of Wembley, that capitalism – so to speak – would trample all over the planned economy.

England, back to their traditional white shirts after their yellow shirts in Poland, started off smartly, favouring crosses from both Poland flanks. Jan Tomaszewski, the Poland goal-keeper who was dubbed “the clown” by manager and part-time TV pundit Brian Clough, seemed to do everything in his power to prove Clough right.

In one early example of his flakiness, he nearly threw the ball at Allan Clarke’s feet before redeeming himself. In another indication that it was going to be an eventful afternoon, Tomaszewski appeared to dislocate a finger before it was pulled back into place.

Tomaszewski had a hectic first-half, interspersing brilliant saves with less convincing ones, swinging from the sublime to the ridiculous. England did pretty much everything but score. In the first-half they forced 14 corners.

There were only three teams in England and Poland’s qualifying group, the third being Wales. Wales had done England a favour by drawing with Poland in one of their two matches but as a result of their loss in Poland, England still had to win at Wembley. Poland would qualify for the West Germany finals with a draw.

As luck would have it, Jan Domarski opened the scoring first for Poland at Wembley. Clarke equalised with a second-half penalty but it wasn’t enough. When the Belgian referee blew the final whistle, the score was 1-1, and England had failed to qualify for the finals.

The Poland side, full of players with difficult-to-pronounce surnames, finished third in the 1974 World Cup. After making penalty saves against West Germany and Sweden and being pretty dependable in goals, Tomaszewski was named the tournament’s best goalkeeper.

The English football historian and journalist, Brian Glanville, has pointed out that the Poland team in West Germany were not the Poland team of Wembley. The team of West Germany, were better, better drilled and more confident. At the same time, this these were heady days for Polish football. With Tomaszewski in the team, they won silver in football at the 1976 Montreal Olympics.

These might have been heady days for Polish football but they weren’t heady days for Polish footballers. Tomaszewski, for instance, was not allowed to play outside of Poland until after he had turned 30. When he did, he played in both Belgium, as did many of his Polish colleagues, and Spain.

He finished off his career as a journalist, goal-keeping coach and pundit, developing a reputation for saying crazy things that raised people’s hackles. He was not fond of those in power, perhaps because his family had felt the jackboot of authority.

At the end of the Second World War his parents were kicked out of Vilnius in Lithuania and told to find a home in Poland. Tomaszewski had that off-the-wall goal-keeper’s sensibility until the very end.

The Wembley draw against Poland was to be Sir Alf Ramsey’s last game as England manager, as he went the way of Moore a couple of games later. Leeds United, under Don Revie, won the 1973/4 league title from Liverpool, so it made sense to make Revie England coach as Ramsey’s successor.

It was an interesting league season – 1973/4 – very much in keeping with the times. The football was not freewheeling. Leeds, the league winners, drew 14 of their 42 league games, exactly a third of their matches. Draws were as common as rainy days and chip butties.

Liverpool, in second, played out 13 draws in their 42 fixtures, while Derby County played out 14, like Leeds. Ipswich Town, in fourth, played 11 draws.

The fact that a win was worth only two points in those days, combined with a preponderance of draws, means that many clubs found themselves close to each other in the middle of the table.

Seven points separated Derby in third from Wolverhampton Wanderers in 12th, Derby on 48 points and Wolves on 41.

You can take this further. Only ten points separated Ipswich Town in fourth on 47 points, from 19th-placed Birmingham City on 37. That’s 16 clubs on a ten-point split. Such cramming in the middle makes every match a dog-fight. If you can’t win, you’re going to make sure you don’t lose.

While 1973/4 was a fine season for Revie’s Leeds United, it was a less impressive one for Manchester United. An old United stalwart, Denis Law, scored against them for Manchester City in United’s last game of the season, a goal which sealed their relegation fate.

Out of decency, I’ll resist the temptation to draw too many contemporary parallels, but leave you with United’s record for the season. United were relegated along with Norwich City and Southampton, finishing three points above City’s 29 points in second-last position. United lost 20 of their 42 games in the league; they conceded 10 more goals than they scored.

A cake is not baked from such crumbs.

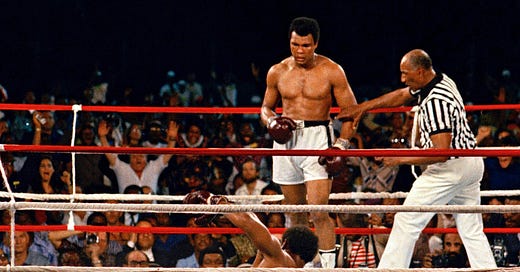

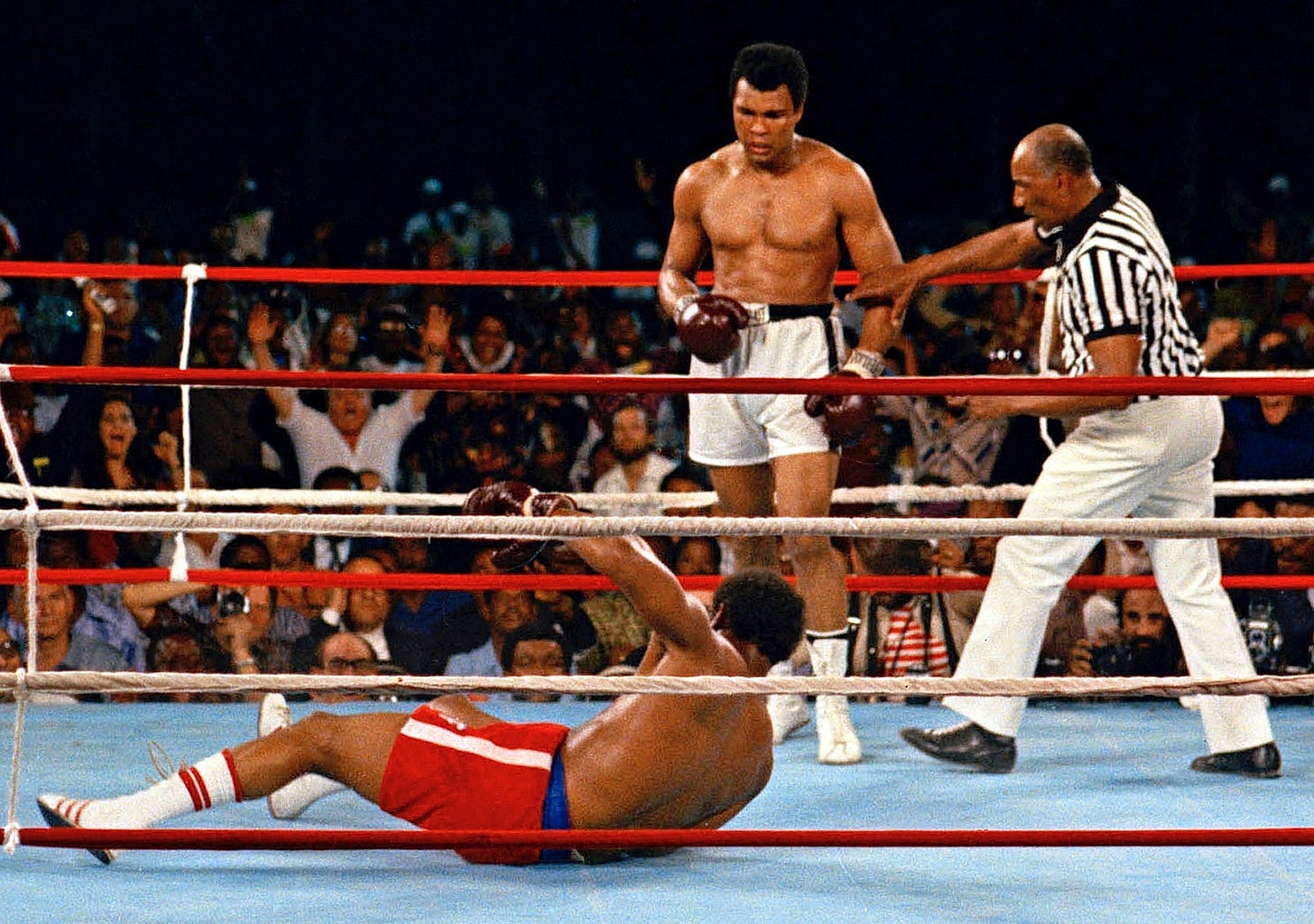

While Manchester United went down, Muhammad Ali merely threatened to go down in 1974, clinging to the ropes in the “Rumble in the Jungle” against George Foreman, the champion, in Kinshasa, Zaire. The strategy was later referred to as Ali’s “Rope-a-Dope” trick.

As the fight progressed, the powerful Foreman tired himself out as he tried to put the defensively-minded Ali down. Ultimately, through frustration and fatigue, Foreman exposed his defences to the quicksilver, counter-punching Ali, who knocked Foreman to the canvas in the eighth round.

Foreman might not have lost the fight early but he failed to endear himself to the locals from the beginning. He got off the plane upon arrival in Kinshasa with his two German Shepherds, dogs that reminded ordinary Zairians of the dogs used by the Belgian colonials prior to independence in 1960.

Ali, by contrast, was friendly and out-going, deft with verbal jabs and rhyming combinations. He was the popular favourite, although widely tipped to lose. The Rumble was not only a fight – it was a cultural event, a jamboree, a happening, with singers and bands, including James Brown and Miriam Makeba, performing beforehand – and journalists and writers, making beautiful sense of it.

After a postponement because Foreman cut his eye in sparring, the fight finally took place at 4am local time to accommodate viewers in North America, where it was shown on pay-per-view closed circuit television, otherwise known as theatre television.

The fight’s American audience ran into tens of millions, although its true number is probably exaggerated. An estimated 26-million watched the fight on BBC. These things should always be taken with a healthy pinch of salt but in some quarters the Rumble has been dubbed as the greatest sporting event of the 20th Century.

One of the commentators that night was American boxing legend, “Colonel” Bob Sheridan. Here he is, 40 years later, saying some blithely off-colour things about Africa in 1974.

Don King, the fight’s promoter, was unable to stage the fight in the US, and the money for the purse and the hotel bills and the happy frivolity came from some shady places. The Libyan, Muamar Gaddafi is reputed to have forked out money for the fight. So, too, did the-then Zairian dictator, Mobuto Sese Seko, on the advice of his American helpers.

By his own admission, Foreman was an angry man in 1974, with only “hate and revenge on my mind”. In later years, Foreman’s attitudes softened. He and Ali became supportive of each other and best of friends. It didn’t happen immediately but Foreman seemed to leave part of himself behind in the Kinshasa ring.

It was an exciting year for sport in Zaire under Sese Seko’s dictatorship. Only one team from Africa qualified for the World Cup in those years. With Sese Seko’s support, the national team beat Zambia and Morocco home and away in the final qualifying stage to book their place in West Germany.

Sese Seko, who came to power in a 1965 coup with American and Belgian backing, overthrowing Patrice Lumumba’s democratically-elected government, is reputed to have given the players a Volkswagen each and lavished gifts such jewellery upon them for their girlfriends and wives.

He invited them to the presidential palace, an offer they couldn’t refuse. They weren’t to know it then, but with Sese Seko’s involvement and his advisors’ prying, their World Cup ordeal was only just beginning.

Having qualified for the 1974 World Cup in West Germany, Zaire were drawn in an awkward group with Scotland, Brazil and Yugoslavia. They lost 2-0 to the Scots in their opener, a by no means embarrassing result, despite the Scots’ manager telling his team beforehand that if they couldn’t beat Zaire, they may as well pack up and go home.

In the days running up to Zaire’s second match against Yugoslavia, the team became embroiled in a payment row over appearance bonuses. It is difficult to say for sure but the Zaire players were either concerned that travelling officials might be siphoning off what was meant for them, or FIFA money meant for them was heading straight back to Zaire – in which case they would never see it.

Either way, fearing an incident, FIFA intervened, offering the team 3000 Deutschmarks per man in compensation, which smoothed ruffled waters temporarily.

Zaire was coached by a Yugoslavian at the time, Blagoje [Blag-o-ye] Vidinić, a former goal-keeper, and he was keen to do well against the Yugoslavs, particularly as he realised after the teams Scotland loss this was do-or-die for them. And they still had Brazil to play.

In the event, none of these things mattered. The team was still disgruntled, a situation compounded by the team going down one, two and three early goals to the Yugoslavs.

Odd decisions didn’t help matters. Kazai Mwamba, their first-choice goalkeeper, was replaced with a far shorter substitute ‘keeper which did little to alleviate feelings of doom. When the final whistle was blown, Zaire had conceded nine goals against the Yugoslavs. Back home, Sese Seko was furious.

The permutations were such for Brazil that they needed to put at least three goals past Zaire in order to qualify for the second round in both teams’ final group game. Zaire were doing well at half-time, only 1-0 down, proving that winning the 1974 African Cup of Nations was no fluke. But in the second-half, disaster, as Brazil netted a second and a third goal.

Raoul Kidumu, Zaire’s captain, has subsequently alleged that the Zaire coach and their goal-keeper, fixed the match, with the ‘keeper letting in two soft goals. The allegation makes sense but how would we know for sure?

Kidumu’s thinking gains credence when we think of another incident from the match, one which has entered World Cup folklore. In the second-half, the Zaire defender, Mwepu Ilunga rushed out of defensive alignment just as Brazil were about to take a free-kick, kicking the ball downfield.

Fans watching and fans at home took this for an over-zealous moment of innocence from the defender, but this doesn’t really make sense, does it? This was an experienced, feted, and well-travelled side.

Ilunga was making a point. By kicking the ball away, he claims, he was trying to draw attention to the fact that the match was in the midst of being thrown, and was hoping to be red-carded. The well-regarded Romanian referee, Nicolae Rainea, the so-called Locomotive of the Carpathians, simply gave the Zaire player a yellow card. His protest fell on deaf ears.

Poor Zaire, unable to score a goal in a tournament they had looked forward to for months, still had to face the intimidating possibility of flying home. Upon touching down in Kinshasa, they were met not by a luxury bus, the mode of transport that had taken them to their waiting plane prior to the World Cup, but a military truck.

They were driven to the presidential palace, where they were harangued by Sese Seko. How could they let him down like this, after all he had done for them? He lectured them for minutes, stressing that they were forbidden to leave the country, like Tomaszewski was forbidden to leave Poland before he turned 30.

If they thought they could further their international careers overseas, they were sorely mistaken. They were obliged to play in the local leagues, where his spies could keep an eye on them, and they earned a pittance.

Other than heavyweight fights and peeks behind the Iron Curtain, what else can we say about the world in 1974? Well, the Swedish super-group, ABBA, had a worldwide hit with Waterloo. Jet airliners fell from the sky with alarming regularity, sometimes the result of hijacking (a common form of political extremism at the time), sometimes because of mechanical failure.

Richard Nixon, the US president, finally capitulated after a long, costly and unsavoury siege otherwise known as Watergate, and the Rubik’s cube became a hidden feature of classrooms across the world.

Roman Polanski wowed global audiences with Chinatown, a film in which Jack Nicholson gave new meaning to the phrase “nose job”, and the Derg took over from Emperor Haile Selassie in Ethiopia. In European news, Volkswagen brought out the successor to the Beetle, the car Sese Seko had given to his players in the hope they would do Zaire proud in West Germany.

The car was called the Golf. Who would have thought golf could provide the name for a car. It has proved just as popular – if not more so – than the Beetle.

One of my favourite stories from 1974, however, relates to the birth of the Chipko movement in two Himalayan villages. Frightened by logging of oak and rhododendron trees around the villages of Reni and Mandal in northern India, a group of women got together to protect their trees, sometimes going so far as to surround them with a kind of human wall.

Not only were the trees a vital source of fuel and fibre, but it was widely felt that deforestation had contributed to a changing micro-climate and massive erosion in the area. After trees had been felled by commercial loggers, floods and landslides became far more common.

The Chipko movement – “Chipko” means “to hug” in Hindi – aimed to address these environmental issues and also, I’m happy to report, made the world a linguistically richer place by introducing us to the phrase “tree hugger,” of which the phrase “bunny hugger” must surely be a derivation.

Elsewhere in the sporting world, West Germany beat the Netherlands in the World Cup final. Poland and Brazil put up good showings too. Jimmy Connors beat Ken Rosewall in what looks from a distance like three suspiciously straightforward sets to take his first Wimbledon men’s titles and South Africa’s Gary Player won the US Masters title at the same time as his rugby compatriots back home were being pummelled by Willie-John McBride’s rampant British Lions.

Late in the year England sent an ageing cricket team to Australia. They suffered with injuries and Colin Cowdrey, well into his forties, had to be flown out. Denis Lillee and Jeff Thomson licked their lips.

I’ve left the best for last. While researching this episode, I watched the first-half of the England versus Poland game at Wembley – the game needed desperately to win if they were to get to West Germany for the finals.

Halfway through the half, something strange happened. An England player was fouled by a Polish defender in the Polish half. Upon hearing the referee’s whistle, the Polish defender rose off the turf, turning his back to the referee helpfully so the ref could record his number. Next, he bowed politely, thanking the referee for booking him. I almost couldn’t believe my eyes. I was totally amazed.