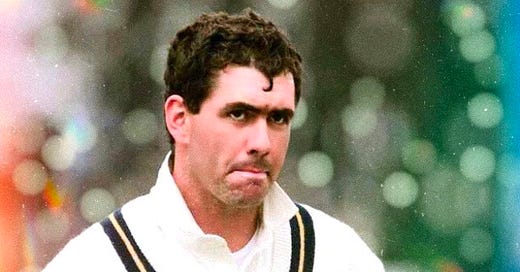

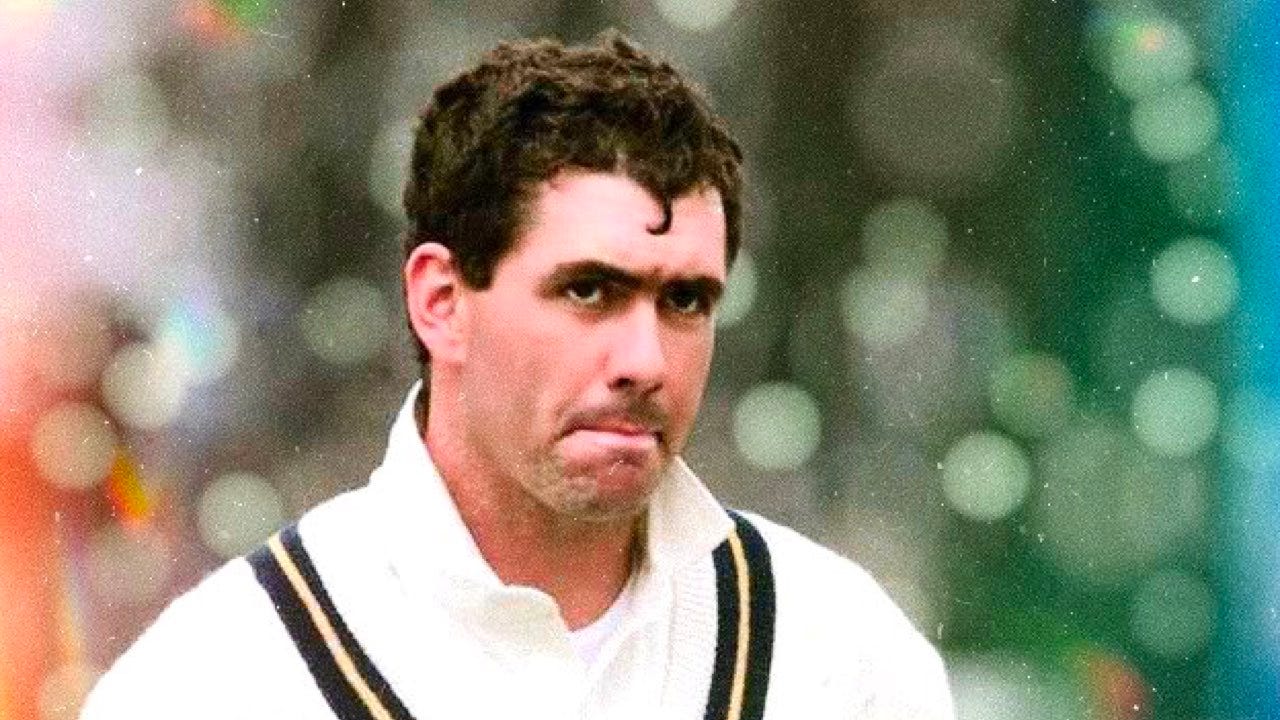

The days of 22 and 23 January 1988 were not auspicious ones for the Cronjé brothers, Hansie and Frans. Just out of Grey College in Bloemfontein, Hansie made his debut for Orange Free State (OFS) in a Currie Cup fixture against Transvaal, with his brother playing only his fourth first-class game for the province. At the Wanderers they faced a Transvaal attack led by the Bar-

badian Rod Estwick, with Clive Rice tucking into his slipstream. The match was over in two days.

Both Transvaal pacemen had a touch of the thug about them and were none too sentimental about a group of upstart Afrikaners who had strayed onto the wrong side of the boerewors curtain. Frans made one and four, while Hansie’s first innings two was improved upon in his second dig, when he scraped 16 in two hours. ‘The Cronjés didn’t do that badly,’ says Gordon Parsons of a side who had recently been promoted to A-Section cricket. ‘Free State managed 160-odd in the first innings and got bowled out for 51 in their second. Hansie top-scored, if I remember correctly. The next bestwas Corrie van Zyl.’

Parsons, an Englishman, wintered regularly in South Africa, and had met Hansie for the first time the previous season at the Ramblers nets in Bloem. He was impressed by the youngster’s willingness to learn, remembering that Hansie immediately asked him how he’d get him out. Parsons replied that because Hansie was a little rigid at the crease, he’d bowl on fourth stump, moving it away, and his guess was that the youngster would go at it withhard hands. It was the beginning of a long friendship, cemented over many a meal at 246 Paul Kruger Avenue, the Cronjés’ home. Hansie’s mom, San-Marie, was famous for her cooking, and there was extra attraction: Parsons rather fancied Hansie’s sister, Hester.

Cronjé’s disastrous first trip to the Wanderers was soon forgotten. Although he struggled – sometimes badly – in first-class cricket, he took to the limited-overs game like a ball of pap to a fishing hook. Parsons remembers a one-dayer against Kepler Wessels’ Eastern Province in which he and the Cronjé brothers played later that year. Wessels had said some mildly disparaging things about OFS in the press and it riled the visitors to St George’s, who were sensitive about being dismissed as a soft touch.

There was more. Wessels was 12 years Cronjé’s senior at Grey College and had recently returned home after playing 24 Tests for Australia. Wessels had beaten a path to the summit of the game and had done so on his own terms. Cronjé idolised him – taking honours against Kepler’s EP would be just the thing. ‘We were bowled out for 180-odd in our 45 overs,’ recalls Parsons with a chuckle. ‘We then ran out Mark Rushmere and Philip Amm went early. Kepler stuck around for 70 and moaned because we peppered him with

bouncers. We won by 13 runs.’

Orange Free State’s new-found first-class status was, in a sense, a family affair. While the young Cronjé brothers were struggling to tame Estwick on a spicy Wanderers deck, their dad Ewie and others had campaigned tirelessly for OFS to take what they believed was her rightful place among the traditional domestic powerhouses of the South African game; he also represented OFS at board meetings and was close to the United Cricket Board’s Ali Bacher. Through Ewie, the Cronjés had a representative in the heart of South African cricket’s decision-making process.

Ewie grew up in the small town of Bethulie, south of Bloem, and had learned cricket from David Marks, the owner of the local Royal Hotel. For young middle-class Afrikaners, advantaged through the 1950s as apartheid began its comprehensive lockdown of South African life, cricket provided opportunities for self-improvement. All you had to do was wear white, rub your bat with linseed oil during long winter nights on the platteland and remember to fold your wrists over the ball when cutting.

Ewie was the only Afrikaans-speaking member of the OFS Nuffield side in 1957. Hansie, by contrast, was part of a dominant Afrikaans-speaking side in his final year at school 30 years later. After the 1987 Nuffield Week he went on to captain the SA Schools with Jonty Rhodes as a teammate and, by the 1989/90 season, he was scoring his first first-class century – for SA

Universities against Mike Gatting’s rebel England tourists.

Parsons says that Cronjé was not only conspicuously ambitious, he was also a good planner. ‘His view was, “If we do get back into internationalcricket I’m going to be ready,”’ says Parsons, a view encouraged when, shortly after Cronjé had scored his maiden ton, Nelson Mandela was released from Paarl’s Victor Verster prison on 11 February 1990. It wasn’t the first time that Cronjé’s path, feted early on as a possible South African captain, intersected

with the crosswinds of politics.

Some 18 months after Mandela’s release, Cronje – along with Faiek Davids and Derek Crookes – was taken along to India as part of South Africa’s hastily arranged first post-readmission tour. Pakistan had withdrawn from their trip to India at the last minute and it was felt that the youngsters – who supplemented the main side – would gain from the exposure. Ewie and San-Marie were invited along as part of a slightly swollen official delegation. India had been a vocal critic of apartheid. Now 100 000 people lined the streets from Kolkata airport to cheer the South African cavalcade as they inched towards their hotel.

At the beginning of the following year Cronjé’s fine domestic form was rewarded with a place in South Africa’s first World Cup squad. Weeks later, he found himself in Barbados, as understudy to skipper Wessels, for three one-day internationals and an Easter Test. South Africa was not yet democratic but the world rushed to welcome her back into the fold. Both within and without, some thought it happened with unseemly haste.

‘Nobody ever doubted for one second that Hansie was the right choice for captain,’ Cronjé’s former headmaster, André Volsteedt, told a BBC Panrama documentary in 2008, and so it came to pass. With Wessels suffering from a hand injury, Cronjé took over the captaincy when the team was in Australia in 1993/4, with the South Africans memorably winning the Sydney Test. The full-time captaincy wasn’t his but it was only a matter of time.

Wessels remained captain for the tour of England in 1994, the first to England since readmission. Matters began on a high note of new flag-draping emotion, with a thumping win at Lord’s. Old ‘Soft Hands’, Peter Kirsten, scored a century in the drawn second Test at Headingley, but matters headed south at the Oval when Fanie de Villiers struck Devon Malcolm flush on the helmet, an affront to which he didn’t take kindly. ‘Don’t ask me that – you guys are dead,’ was Malcolm’s response to Allan Donald’s question about whether he was all right, as he felled the South African batsmen like skittles. He took nine for 57 in the South African second innings, England winning the Test and so squaring the series.

Cronjé had a miserable time in England. His dismissal to Malcolm in the second innings at the Oval was a case in point: he was too late on the shot, bowled by a delivery that beat him for sheer, breath-taking pace. The selectors were suddenly worried: Out of his comfort zone in England, Cronjé looked troubled. Was he the right man to take over from Wessels?

They dealt with their unease about Cronjé and others – such as Andrew Hudson – both adroitly and with a touch of expedience: by sacking Mike Procter, the coach. By the time the team toured again, playing in the Wills Triangular in Pakistan with the hosts and Australia, a new gaffer was driving the team bus. His name was Bob Woolmer and he was a man for whom the word soutpiel could have been invented. Having grown up in Kent, he had relocated to Cape Town in the 1980s after playing 19 Tests for England. An assiduous thinker about the game, Woolmer interviewed better than his rivals and brought best practice and creativity to the job, qualities Procter conspicuously lacked.

Against Woolmer’s better judgement, Wessels remained. He had turned 37 the month before the tour to Pakistan in October 1994, but such were the concerns about Cronjé, the captain-elect, that he soldiered on. Although the South Africans lost all six matches, Cronjé was in sublime form, rounding off South Africa’s last game with a not-out 100 against Australia. Despite South Africa failing to reach the final, he was the competition’s leading scorer, making Wessels’ retirement all the easier. And so Wessels the warrior walked into the sunset with the characteristically grim dignity that had made him such a reliable performer in the early readmission years.

Cronjé’s first Test in charge was against Ken Rutherford’s New Zealanders at the Wanderers, which they lost in an atmosphere of finger-pointing and recrimination. A win at Kingsmead in Test two levelled the series but such was the quality of Barry Lambson’s umpiring in the third Test at Newlands that Rutherford became apoplectic. He was incandescent that Lambson hadn’t given Cronjé out when he feathered an edge to the ’keeper on his way to a match-and-series-winning 112.

At the end of Cronjé and Woolmer’s first full season together, Cronjé married his childhood sweetheart, Bertha Pretorius. Shortly afterward, he started as Leicestershire’s overseas professional, a position finessed by Parsons. During a busy county season, there were opportunities for fun. The young couple attended Wimbledon, where Hansie was mistaken for Pete Sampras. There was a trip to Paris where, according to Hansie’s sister Hester, ‘They lived on bread and water – he was such a cheapskate, he was always giving away his freebies as Christmas and birthday presents.’

As the seasons rolled on, fun seemed in increasingly short supply. Towards the end of the team’s first full-fledged tour to India since readmission, Cronjé entertained thoughts of throwing the third Test in Kanpur; the team also considered a match-fixing proposition, after having had their arms twisted into playing in Mohinder Amarnath’s benefit match, which wasn’t on the original itinerary.

The following season, a young man from the Eastern Cape by the name of Makhaya Ntini was forced on Cronjé in a home series against Sri Lanka. As a farm boy, Ntini had warmed his shoeless feet in cow pats as a child, and so impressed cricket scouts that he was given a bursary to Dale College in King William’s Town, where he blossomed.

He survived a rape trial to become the UCB’s poster boy, and Bacher thought it politically appropriate to shoehorn him into the national side. Cronjé was having none of it; Ntini hadn’t served a domestic apprenticeship, Hansie argued, but his protestations were in vain. Ntini made his debut against the Sri Lankans of the Newlands Test of March 1998, taking the first

of what was to turn out to be 390 Test wickets.

The young skipper took on an increasingly beleaguered air. He turned out briefly alongside the abattoir workers and painters of amateur Ireland as an overseas professional, a decision that unambiguously said to Bacher and his cohorts: ‘Be careful, you might lose me.’ The following season, during the West Indies’ first visit to the country, South Africa fielded an all-white side against the visitors’ all-black one in the first Test. The controversy was immediate. Herschelle Gibbs, a coloured, was drafted into the side in the place of Adam Bacher, Ali’s white nephew, for the second, but such tinkering did little to placate the politicians. A rancorous season, amped-up by an insensitive speech at Newlands by then UCB president, Ray White, ended in

Cronjé resigning, a decision later rescinded.

The problem was clear: Cronjé was never quite as liberal as the times demanded. He, whose political attitudes had been formed in the old South Africa, was expected to usher in the new with the blithe sweep of the politician’s practised hand. He couldn’t always do it.

As the decade funnelled to an end, Cronjé and politicians such as Bacher circled each other increasingly warily. What had started so warmly with Woolmer also began to sour. Consecutive World Cup eliminations in 1996 and 1999 didn’t help, the second in excruciating circumstances in the tie at Edgbaston, a muddle memorably captured by the Daily Telegraph’s Scyld Berry ‘as the day when time and Allan Donald stood still and Lance Klusener kept on running’.

Having toured India in 1991 as the happening youngster, Cronjé was in the public eye throughout the decade, South African sport’s first celebrity skipper. Lucas Radebe graced the throne all too briefly, hobbled by injuries. Francois Pienaar might have occupied the position too, but his reign as Springbok player and captain was dazzlingly brief, over in 29 Tests and

three years, 1993–1996. Cronjé was in the public gaze for triple that time, 1991–2000, longer if one takes his post-cricketing life into account.

It was a time during which Afrikaner politicians retired almost completely from the public realm. Into the vacuum flowed Afrikaans-speaking sportsmen and public intellectuals such as Max du Preez and Antjie Krog. Cronjé became the go-to man for young and old Afrikaners alike; he also

became a notional figurehead for all that was perceived as good in the fragile post-apartheid consensus – a new man for a new age. Here was uncharted territory, conducted almost exclusively in the glare of public opinion. It was a difficult burden to bear.

Cronjé’s dislike of political compromise was one thing, the tragic flaw in his personality quite another. He loved money so much that he was motivated to do wrong for it, a fact known by White and one therefore almostinevitably known by Bacher. Not enough was made of the flirtation with easy money during the Kanpur Test in 1996 ahead of the Amarnath benefit match, not initially scheduled, and hastily tacked on to the end of a punishing tour without the players’ consent. Woolmer didn’t see fit include anything in his post-tour report and by the time a new coach, Graham Ford, took South Africa to India next, institutional memory had been lost. Cronjé accepted the gift of a cellphone while on tour there in 2000 and, unbeknownst to him, his conversations to illegal Indian bookies were taped. Cronjé’s web of deceit, his undelivered-upon promises and his manipulation, had begun to disintegrate.

Cronjé’s initial denials that he’d been involved in match-fixing were met by chest-thumping agreement by the vox populi. Then a handwritten confession and a teary press conference in Durban in April 2000 ahead of an ODI series against Australia. The bookie, Marlon Aronstam, who had waltzed into Cronjé’s hotel room during the last Test of the home summer against England before the India tour, thought Cronjé had been pressured into blinking first. The Indian police had no transcripts. ‘It was his word against theirs – he needed to ride it out,’ said Aronstam.

Instead, Cronjé unravelled. It became apparent that the idea for each side to forfeit an innings at Centurion against England was not his but Aronstam’s, an act of audacity for which Cronjé received R50 000 and a leather jacket for Bertha. While in India weeks later he was receiving upwards of 50 to 60 cellphone calls and text messages a day, as he jokingly floated the idea of under-performing in a Test with Lance Klusener, Mark Boucher and Jacques Kallis.

Later in India, with the five-match ODI series already lost, he conspired to involve Gibbs and Henry Williams in under-performing in the fifth ODI in Nagpur. Ever the charming loskop, Gibbs forgot the instructions; Williams injured himself and couldn’t complete the second of his 10 overs. Ironically, South Africa won the match, losing the ODI series 3–2.

Cronjé’s confession prompted the King Commission, a soap opera replete with pantomime villains (Aronstam), feisty public prosecutors (Shamila Batohi) and comically unreliable witnesses (Pat Symcox and Daryll Cullinan). Judge Edwin King had begun proceedings by striking the appropriate high note, telling Cronjé that ‘the truth shall set you free’, but with hindsight, we see that the Commission’s intention was palliative. Woolmer wasn’t called as a witness; neither was Wessels. White, who had a sometimes tetchy relationship with Bacher and was less likely to coat his answers, would have proven invaluable in answering questions. It would have been illuminating, for instance, to hear his answers about the ‘lost’ 1996 tour report to India.

All this was conducted in the deforming glare of the television cameras, a place Cronjé had occupied, on and off, since his first tour to India in 1991. Essentially an outlier (apartheid-educated, Afrikaans-speaking, from South Africa’s most maligned province), Cronjé was not only ill equipped for the diplomacy demanded by the times, he was the country’s most scrutinised celebrity sportsman. The pressures he faced were unique, the erosion slow and cumulative. By the end he was lost in a moral wilderness, having breakfast with Aronstam the bookie and his son on the morning of a Test, entertaining thoughts of corrupting the match. Cricket – a sport of boundaries both actual and moral – had, under Cronje’s perverting touch, revealed itself to be effectively boundary-less, a moral degree zero. ‘When I told my friends about having breakfast with Hansie, they couldn’t believe it,’ said Aronstam.

Neither could we.