South Africa's Last Great Tennis Win

50 years on: the bizarre story of the 1974 Davis Cup victory

THE 1974 SA Tennis Open at Johannesburg’s Ellis Park contained a pretty perky field. The men’s draw showcased five of the world’s top ten, including Jimmy Connors and Arthur Ashe, who would go on to contest that year’s final, and 12 of the world’s top twenty.

The women were represented most notably by Chrissie Evert, whom Connors was, ahem, courting at the time. All the players were staying at the Landdrost Hotel, just round the corner from Ellis Park, and although Jimmy and Chrissie were staying in different rooms, they found time in the evenings to – as it were – break curfew and indulge in some spirited serve-and-volley stuff.

As well as being popular and well-patronised, with room for about 6000 fans – some went so far as to call the SA Open the unofficial fifth Grand Slam event – the 1974 SA Open contained a remarkable sideshow almost forgotten by history.

A month prior to the Open, South Africa’s Davis Cup team had won the Davis Cup, the first time ever and the only time since.

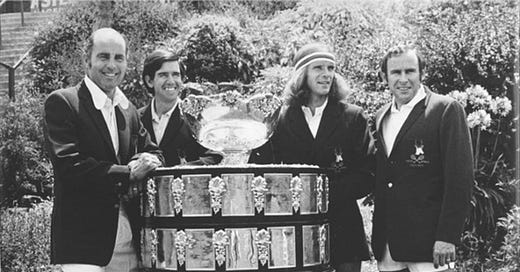

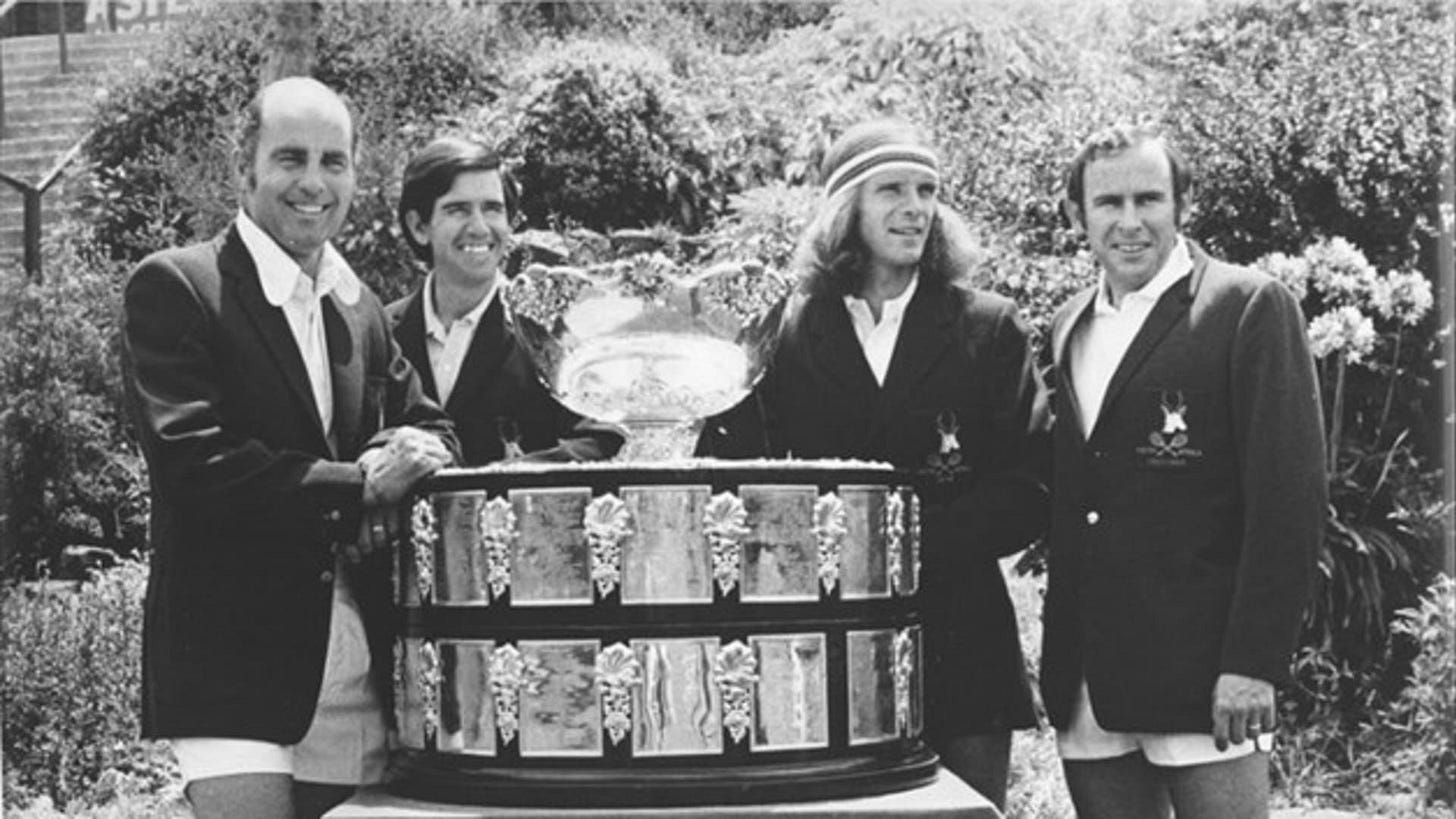

Most of the South African team who had won the Davis Cup a month previously were playing in the SA Open, so it made sense for the Davis Cup itself to be handed over during the Open. Blen Franklin, the president of the SA Tennis Association and a supreme court judge, duly handed the Cup over to Claude “Skip” Lister, the captain of South Africa’s Davis Cup team.

It was a moment of bathos unlikely to ever be rivalled in South African tennis.

The players in whites and green Springbok blazers, were in attendance, as were the press and a couple photographers. The players were, other than Lister: Ray Moore, Cliff Drysdale, Robert Maud and the famous doubles pair of Bob Hewitt and Frew McMillan. Poses were fixed, smiles assembled and photographs taken. After a few moments the group shuffled off one on the grass embankments at Ellis Park to resume their part in the tournament.

There was not an International Tennis Federation (ITF) official in sight, in fact, their only representative, so to speak, was the David Cup trophy. The conclusion to the 1974 Davis Cup had proved to be a singular embarrassment to all concerned.

“We were proud to see our names on the Davis Cup,” Hewitt told the New York Times in 2009, “but the way we got it left a sour taste in our mouths.”

So why, you are doubtlessly asking, did a high court judge hand over the Davis Cup at the 1974 SA Open? And why were South Africa’s opponents not present? Did the final even get played?

Well, let’s answer the last question first because this answer will also provide us with answers to earlier questions. The final, meant to have been at Ellis Park, although neutral venues in Europe were discussed, was never played. It was never played because South Africa’s opponents in the final, India, refused to come to South Africa in protest against apartheid.

India’s refusal gave the Davis Cup organisers no alternative but to award the Davis Cup for 1974 to South Africa. The official explanation of the “victory” was by “walkover.” It remains one of the most inconclusive, bittersweet and unsatisfactory episodes in Davis Cup history, all the more so because each team believes that they would have prevailed in the final to this day.

And there’s a further level of dissatisfaction, too. India’s non-participation in the final was influenced by none other than Indira Ghandi, the-then Indian prime minister. Ghandi’s wishes were finally obeyed but this didn’t mean that members of the Indian team didn’t try to convince her otherwise.

Vijay Amritraj, one of two Amritraj brothers in India’s Davis Cup team, sat down with Ghandi for an hour to try and persuade her to allow the Indian team to travel to South Africa. He was received courteously, and listened to, but Ghandi’s mind was made up.

The Indians were frustrated by their government’s intransigence for several reasons. Up until 1974, the Davis Cup had historically been dominated by only four nations, the USA, Great Britain, France and Australia.

India were beaten finalists in 1966, true, but the Amritraj brothers knew that a final against South Africa would be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. They were also battle-hardened, because their journey to the final that year had been long and challenging.

In getting to the final, they needed to beat Australia and the Soviet Union, so they were well grooved. The rubber against Australia was particularly memorable, a tennis marathon that generated a mammoth 327 games across the singles, the doubles and the reverse singles.

The doubles, which pitted the Amritraj brothers against the Australian pair of Colin Dibley and John Alexander, was instructive in this regard. The Indians took the first set 17-15, but lost the second 6-8; they won the third, a mere appetizer to the gigantic set to follow, 6-3, before losing the humongous fourth to the Aussies 18-16. Finally, at two sets-all, the Indian brothers prevailed, taking the fifth set to go into a 2-1 lead after three rubbers.

It was this kind of tenacity that led the Indians to believe they could fly into Johannesburg and prosper. But they were never given the chance to find out and, in a manner of speaking, they have been playing the final they never played, ever since.

By contrast, South Africa, playing at altitude on the Highveld in Johannesburg, believed they had the beating of India. Their singles team, likely to have been Moore and Drysdale, would have been too powerful for the Indians, and their doubles pair, of Hewitt and Frew McMillan, was amongst the most crack doubles pairs in men’s tennis at the time.

Johannesburg is a city built at nearly 2000 meters above sea level, so the rarified air provides challenges for breathing. The ball also bounces higher on the Highveld, sometimes wondrously so.

The South Africans noted that India’s wins over Australia and the Soviet Union had both taken place in India, in Calcutta and Poona, respectively. They wanted to see the Indians deal with the lack of air and the bounce of the ball on the Highveld, and reckoned the Indians wouldn’t be up to it.

The South Africans, too, had taken a long and circuitous route to the final, and were also the better for it. That year’s Davis Cup draw stipulated that the South Africans played against mainly South American opposition in the tournament’s early stages.

First, the South Africans had a walkover against Argentina, who would not play against the South Africans on political grounds, before struggling on clay against Chile in Colombia’s Bogotá to win 3-2. The win against Chile meant they had to face Colombia, who were at home, in the Americas Inter-zone final, a theoretically tricky tie.

Ray Moore beat Ivan Molina in four sets to get the South Africans off to the perfect start, before Hewitt won his singles against Jairo Velasco in three. Hewitt and McMillan won the doubles rubber, only dropping six games in three sets and the tie was South Africa’s. They would have tougher opposition as the Davis Cup continued.

Italy, meanwhile, had scraped past a Romanian team featuring Ion Tiriac and Illie Năstase, and now needed to make their way to Johannesburg for the semi-final. In the first of the four singles ties, Hewitt took on Antonio Zugarelli. The tie went to a fifth set, the South African finally prospering 6-1 against the fast-fading Zugarelli.

After losing the first set to Adriano Panatta, South Africa’s Moore won sets two, three and four and, in the doubles tie, the redoubtable duo of Hewitt and McMillan only took three sets to dispose of Panatta and Paulo Bertolucci, although the third set did go 10-8 to the South Africans.

With the win in the doubles, the tie was over, the home side eventually winning 4-1 on their way to the final they didn’t know then wasn’t going to be played.

Neutral venues were duly discussed at ITF level. The South Africans weren’t opposed to a neutral venue in principle, but were concerned about anti-apartheid protesters, who were gaining traction through the decade.

There were incidents in Hilversum, in the Netherlands, as well as Germany at roughly the same time and Byron Bertram, and occasional member of the 1974 Davis Cup side, remembers an incident at Newport Beach, California, in 1977 where the South Africans were playing a Davis Cup tie.

At the beginning of the third set of the doubles, with the American pair of Stan Smith and Bob Lutz playing McMillan and Bertram, two protesters rushed from the stands and poured motor oil on the court’s surface. The American captain, Tony Trabert, intervened, as did the police, Trabert hitting one of the protesters with his tennis racquet before they were carted away. Speaking about the Newport Beach tie, Bertram told me: “Looking back, it should never have happened.”

After much coming and going, the idea of a neutral venue was shelved by both the ITF and the South Africans. The South Africans knew they had a winning ticket at Ellis Park and some believed that the Indians were secretly relieved they wouldn’t have to travel because they were likely to have lost a Johannesburg-based tie.

There was great irony in the fact that the 1974 Davis Cup was handed over at the SA Open, because the Open had been an open to all races event since Owen Williams insisted that it be open in 1968. Ashe, of all players in the world at the time, was crucial in giving the tournament a credibility it so desperately lacked, but was initial adamant at first that he’d go nowhere near South Africa.

“I would sooner see an atomic bomb dropped on Ellis Park than set foot anywhere near it,” Ashe had famously said in the late 1960s. He was in no rush to change his mind.

But Williams worked on him, sometimes daring Ashe, sometimes encouraging him, to change his mind. Williams finally persuaded Ashe to come and see for himself. The 1972 SA Open became Ashe’s first, a public relations coup for Williams.

Ashe warmed to South Africa enough for him to come again. He was there in the 1974 tournament – remember, he lost to Connors in the final – and, whether he was hoodwinked or not, he retained an open mind on matters South African.

Here is a rare recording of Connors after beating Ashe in the final 1974. Note the good-natured jibe about the linesmen, with whom Connors had a couple of skirmishes on the road to victory.

Not that it was always socially comfortable for Ashe to be in South Africa. In the early 1970s it was customary for players participating in the SA Open to be housed not in hotels but to be billeted at the homes of well-to-do tennis patrons in their often-luxurious Johannesburg homes.

The story is told, for instance, of Ashe, sitting on the patio of one such Upper Houghton home when he was approached by a servant in a starched Victorian uniform. He was addressed by her as “master”, which made him desperately uncomfortable, and asked if he would like tea.

In another oft-repeated anecdote circulating at the time, Thorben Ulrich, the bohemian Dane, was housed at another swanky home. He made himself comfortable, which, of course, meant doing yoga in the family lounge. The lady of the house was slightly non-plussed to wander into the lounge to find Ulrich, sitting cross-legged, staring at a tennis ball suspended from the chandelier.

She also noted with alarm that Ulrich was naked, but had enough presence of mind to compose a quick question. “What are you doing, if I may ask, Mr. Ulrich?” The reply? “I am focusing on a tennis ball, madam, ahead of my game tomorrow.”

A music journalist in later life, Ulrich was very much his own man. In the early 1970s he participated in one of the satellite tournaments around the SA Open, and this one happened to take place in East London on the South African coast.

On the day before the tournament was about to begin, Ulrich arrived at the gate, asking to be let in for an hour or two of practice. Security refused, despite Ulrich showing them his kit and collection of racquets.

“We do not encourage the participation of hoboes,” security are alleged to have responded, although, this being South Africa, they probably did so in language harsher and less refined.

Ulrich sitting naked humming at a tennis ball suspended on a chandelier and Ashe’s embarrassing encounter with a maid calling him “master”, finally persuaded Williams and his second-in-command, Keith Brebnor, to move the players to upmarket hotels. Life became simpler as a result, although not nearly as rich a terrain for risqué anecdotes.

The SA Open was not an event without standing on the social calendar. Two of the honored guests at the 1968 Open were Dr. Christiaan Barnard, who had recently placed Denise Darvall’s heart into the chest of Louis Washkansky, and the Italian actress, Gina Lollobrigida. We do not know whether Chris lost his heart; or perhaps Gina lost hers? What seems pretty certain is that the two indulged a set or two of off-court hanky-panky when play had finished for the day.

In later years, Liz Taylor and Richard Burton were guests of the Open, and in 1974, when the Davis Cup trophy was handed over on the grass embankment, one of the invited VIPs was the actor, Charlton Heston.

Heston was a man of many shades because not only did he allow himself to come to South Africa as a self-confessed supporter of anti-racism and Civil Rights, but he allowed himself to be dressed up in a Zebra-kin kaross at the 1974 tournament as he played in an exhibition match with Ashe amongst others.

Williams, the tournament organiser, must have been a very persuasive man. Not only did he manage to get Ashe and Heston to South Africa but, before the arrival of both, he offered an invitation to the 1968 Open to the African-American player, Bonnie Logan, which she accepted.

Logan is largely forgotten now, a player who seems to have slipped into the tramlines of time, but in her day, she was a rare sight in a very white world.

Although she came to the SA Open in ’68, hers was not a glittering career. In fact, it was one she needed to curtail prematurely because she just didn’t have the means at her disposal to keep it up.

Williams, the tournament organiser, strikes one as a dynamic and interesting figure. He was energetic, smooth-talking and quick on his feet, so much so that I’m sure he occasionally indulged in a little top-spin here and there. He was able to get Ashe, Heston and Logan to South Africa by force of argument alone, giving the SA Open a prestige which some might say it didn’t really deserve.

It is strange to think that even as he was doing his damnedest to keep the SA Open flourishing, as was Brebnor, history was attacking the tournament – and South African sport – from a different angle. The Indians’ failure to come to South Africa was a demonstration that the rest of the world took an increasingly dim view of apartheid. This view was only sharpened as the 1970s continued.

In 1978, with South Africa again playing the USA (the 1977 tie was in Newport Beach) a peaceful march occurred in Nashville, Tennessee, when between 1500-2000 people marched in Nashville to protest against apartheid and the presence of an all-white South African team in their city.

While the very notion of the Davis Cup might not have been in crisis in the late 1970s, the competition certainly hemorrhaged credibility. The 1970s were a highly politicised age, and sport was fair game for anti-establishment protesters or governments keen to score political points.

At the same time, the world was a less homogeneous place than it is today. Repressive regimes, like those in Chile, South Africa and Rhodesia, were increasingly vulnerable to rejection and boycott from teams reluctant to play against them.

The Davis Cup was no exception. The second half of the 1970s saw a flood of withdrawals, protests and walkovers. And, in 1976, the USA became irritable with what they perceived to be a free-for-all.

They alleged that the tournament organisers were too permissive with countries scoring cheap political points, and greater sanctions for withdrawals should come into play. The USA were later joined by France and Great Britain, with all three threatening to withdraw from the competition entirely.

The Davis Cup organisers took note. The Soviet Union, for instance, refused to play against South Africa in the 1978 Davis Cup. As a result, they had their invitation to the 1978 tournament withdrawn entirely. Taking a harder stance softened the “Big Threes” orneriness. The Show must go on.

South Africa’s 1978 Davis Cup was their last Davis Cup for 14 years. They had been banned from entering the tournament briefly, 1970 to 1973, but were re-instated in 1974, which makes their winning of the tournament and the circumstances around it that year, all the more curious.

But, finally, the rest of the world couldn’t be bothered with South Africa. Apartheid was odious, yes, but South Africa’s continued presence on the Davis Cup schedule simply became too onerous. The events at Newport Beach and in Nashville in successive years were small but they had ripples.

And those ripples pulsed through the world. The best way to deal with the stink that was South Africa was not to hold your nose but tell the South Africans that they were unwelcome at the world party in clothes that smelled. When they’d dealt with body odour they could be re-admitted into a sweeter-smelling world.

The Davis Cup itself in 1974 has its own story. In 1974 the Davis Cup was without replica. The Cup was duly sent to South Africa and stored in the vaults of a local bank. The International Tennis Federation, under whose auspices the Davis Cup fell, were slightly anxious that the Cup might not make it back, so they commissioned a photographer to take detailed photos of the Cup, along with equally detailed measurements of the cup’s circumference and height etc.

The Cup did come back, unharmed and in its original form. It didn’t stay in South Africa for long. Perhaps because – in a strange way – South Africa wasn’t really meant to have it.

The following year, Sweden won the Cup, with the legendary Bjorn Borg in her team, and the year after that, Italy travelled to Santiago in Chile for the final. Against the predictions of many, they won it for the first time in their history. The following year it was won by Czechoslovakia. The stranglehold on the Davis Cup had been broken.